|

“God did not make all men equal,” Westerners were fond of saying, “Colonel Colt did.” When it came to the use of shooting irons, however, some men were more equal than others-a fact gunfighters knew well. Top improve the odds of landing on the right side of this equation, they exerciresed meticulous care in selecting their firearms from among the weapons available. As is evident here on the following portals, they had a wide range of choices.

From service in the Civil war, thousands of frontiersmen, inherited handguns-revolvers whose rotating chamber held several rounds. They fired kind of roll-your-own ammunition consisting of a ball, powder and a percussion cap. But the ammunition was all too fallible: unless carefully loaded, it might misfire or even set off chain-reaction detonations of the rounds in the adjoining chambers.

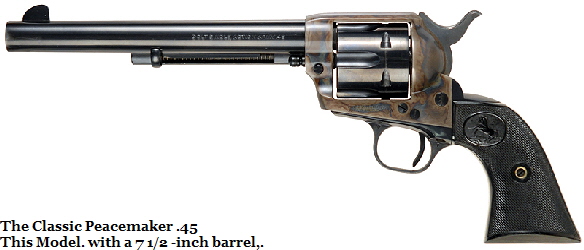

The development of metallic cartridges soon solved these problems. The first metallic-cartridge revolver to be adopted as the standard sidearm of post-war Army was the mordantly misnamed Colt’s Peacemaker of 1873. Sold in enormous numbers on the open market and by mail, this single action-i.e., manually-cocked pistol swiftly became the weapon most likely to be whipped from the holsters, waistbands or leather lined coat pockets of Western gunfighters.

But the reliable peacemaker, along with its imitators and successors, had a drawback. The relatively short barrel-eight inches or less-reduced the power and accuracy. While an expert might consistently hit a stationary man-sized target at 40 yards, effective revolver range in the chaos of combat was less than half that figure. Most gunfighters therefore enlarged their arsenals with a rifle or shotgun.

Even with one of those bigger weapons for deadly firepower, and revolvers for close work, some gunfighters felt less than fully equipped, so they added a vest-pocket pistol to their array of iron. Although woefully inaccurate, a small hidden firearm possessed a matchless potential of surprise, and more than once proved a trump in the hazardous games of men who lived by the gun.

The man whose name was stamped on the most famous gun in the west did not live to savour the triumph. Samuel Colt-a Yankee who developed the first practical revolver in 1836 and went on to earn a fortune and the honorary title of colonel in the Connecticut militia-died a decade before his company came up with its classic creation. But the 1873 Peacemaker was a worthy extension of his genius, and a total of 357,859 of them would be produced by the Colts Patent Fire Arms manufacturing Company of Hartford.

Fighting men everywhere considered the Peacemaker’s balance and durability superior to that of other revolvers of that day, and they expressed their appreciation by clamouring for a variety of versions-some decorative or modified for fast draw, other plain, all lethal.

Colts competitors tried hard to skim sales from the Peacemaker, Smith & Wesson won an endorsement from Buffalo Bill Cody, and Remington got a resounding plug from Frank James-“The Remington is the hardest and the surest shooting pistol made,” he declared-although his brother favoured a rival product (Smith & Wesson Schofield .45).

Both the Colt Company and other gun manufactures wooed customers with an alternate kind of revolver design: double action. In double-action weapons, squeezing the trigger performs the double duty of drawing back the hammer, then releasing it. But even this dividend of simplicity-and a shade more speed-failed to make the Peacemaker obsolete, and in effect its rivals were all competing for second place.

Easy stashed away firearms-whether pocket revolvers or the one- or two shot pistols known as derringers after the pioneering Philadelphia gun maker Henry Derringer-often were hidden in bar girls’ bodices and faro dealers’ sleeves. Even the toughest gunfighters used them as back-up weapons. One Arizona lawman carried upward of half a dozen petite pistols on his person.

But the scaled down size of these guns cost heavily in accuracy and range. Mark Twain, who packed a pocket model Smith & Wesson .22 on his travels through the West, was guilty of only mild exaggeration when he wrote, “It was grand. It only hand one fault-you could not hit anything with it.”

With a mean-looking pistol and a steely eye, a gunfighter might deter would-be foes by appearances alone.

But when combat was inevitable and circumstances permitted a choice of weapons, any sensible gunfighter would reach for a rifle or shotgun-preferably the latter. Rifles and carbines (light, shorter-barrelled rifles) were accurate at ranges often exceeding 200 yards and, with lever actions and calibrated sights, were simple to operate. While shotguns had only about a fifth of the range of rifles-or even less if their barrels were sawed off for easier handling-no weapons in the gun fighters arsenal was more fearsome, since a buckshot load at close range could practically cut a man in two.

Please note: This website is still under construction.

Frequently asked Questions on California Gun Laws...more

Gun Owners hope to win the right...more

Western Store <> Western Writers <> Western Stars <> Western TV <> Country Music <> Guns <> Western Vacations

Western Hand Guns <> Repeating Rifles <> Hollywood Guns <> Gun Safety <> Ricardo Dos Reis